June 26, 2013

No Comments

I live in Seaside Jew Jersey. Our claim to fame is that we’re only an hour from Atlantic City. I run a motel right across the street from the ocean. “By the Wayside Motel,” the brochure reads: “42 Suites, All with Ocean View. C’mon. Get Happy.”

I didn’t write the copy. The brochures were left by the previous manager. “Suite” is pushing it. The rooms are standard-issue coastal motel, but it sounds good. The graphics exaggerate too. The wide-angle photograph on the cover makes the swimming pool look gigantic, when actually more than three people in it at once can create a tide.

I don’t know where the name “By the Wayside” came from. The man I bought the place from wasn’t the original owner. Hard by the water like it is, the name doesn’t exactly fit. All the other hotels and motels up and down the beach have predictable names like Coral Rest, Ocean Spray, and Neptune’s Inn.

I spotted it right away when I first came here. It stood out because of a life-size statue of Peter Pan on the front lawn. Apparently the owner was a diehard fan of the character and had commissioned a sculpture so he could look at him every day. Although I had barely enough money for the down payment on the place and had to mortgage it to the hilt, Peter Pan was what sold me: I desperately needed some whimsy in my life, a reminder of fairy tales and stories with happy endings.

The rooms are full right through the summer, families from New York and Philadelphia mostly, who come for two week holidays with their kids. When I took it on, five years ago now, I had no idea how much work it would mean. I’ve learned that people who have only two weeks a year of complete freedom expect a lot. June to September, I barely have time to breathe. I’m called on to be a concierge, tour director, chamber maid, and confidante, name it. I get asked for the weirdest things, like the mother who wanted baby aspirin at three in the morning, or the couple in Room 34 last year wondering where they could rent a video with a title I wouldn’t repeat out loud. Days run into one another with a constant stream of people in the front office, checking in or out, looking for beach towels, asking where they serve the best steamers.

Come fall, the mass exodus begins and we have Seaside to ourselves again. About half the rooms are closed during the winter to save on heat. Business dribbles in though, salespeople traveling up and down the coast who check in late and leave early, and the odd straggler on his way home from Atlantic City, hung over and broke from a gambling spree. Josh was the only permanent resident here when I arrived: Hazel, Max and Seymour have all come since, my “year-rounds” as I call them. The reason they all ended up here was because I have the cheapest off-season rates in town. It certainly isn’t because of the decor, which is vintage 1950, complete with lime green leatherette couches in the lounge and arborite headboards on all the beds. The balconies are flanked with sheet metal cut out in diamond shapes of orange, red and blue, trying desperately to look like stained glass. My first day on the job was in the middle of a bitter January, with the wind coming straight off the ocean. The motel was almost empty. I was in the front office behind the desk trying to figure out a disorganized set of books and losing patience, wondering why a housewife from Minneapolis ever imagined she could manage a motel. Josh appeared at my desk and handed me a large bottle of gift-wrapped perfume. “Welcome. I’m Josh,” he said, extending his hand gallantly. “I hope you don’t think me too presumptuous. But from afar with that wild hair of yours and those Nordic features, you just screamed “White Shoulders.” I told him it was a fragrance I’d always loved, that its smell reminded me of things that happened long ago. When I told him my name was Moira, he rolled his eyes dramatically. “Of course. It’s perfect.”

We sat behind the desk for the next two hours drinking hot chocolate. Josh couldn’t have been more than 40 but he was completely bald. I learned he envied anyone who had more hair than he had. Before coming to Seaside, he’d been a successful actor in New York until his hair started to fall out mysteriously and he lost what he called “the edge to his performance.” He said he’d find clumps of blond hair on his pillow in the morning and his shower drain finally stopped up altogether. He’d made the rounds of specialists and clinics but no one could come up with any answers. “When a playwright wants to portray a loser, she makes him bald,” he tells me wistfully.

Josh bartends nights at the “Fork N’Cork,” a restaurant down the beach where he says he’d never be caught dead under normal circumstances. But desperate times call for desperate measures, Josh says. Fish nets, dyed red, festoon the walls. Hanging from the netting are giant plastic lobster claws and clam shells painted with maniacally happy faces.

Josh lives in hope of hair. Packages are always arriving in the mail for him, potions and ointments he’s ordered from tv ads which promise hair regrowth. He comes down to the office in the mornings, fresh from the shower, his head in a turban, awaiting each new miracle. I’d seen his scrapbooks of theatre flyers and newspaper clippings and in one photo there is Josh with a full head of platinum blond hair, on the stage of the Bleaker Street Theatre, playing the part of the gentleman caller in a production of “The Glass Menagerie.” Max asked him once why didn’t he try a toupee. Max was a Czech, with a dense, wavy mop of black hair. Josh glared at him.

“This from a man whose hairline starts just slightly above his eyebrows,” he sniffed. “Anyway, toupees always look like fresh road kill pasted on the scalp.”

“What thees mean, thees road keel?” Max asked him, perplexed. Max lives in 4B, the only two-bedroom I have. He sleeps in one: the other is filled with his equipment — plastic bowling pins, stilts, card tables, clown costumes. In summers, he’s a roving entertainer on the boardwalk. Nights, he performs in a revue in Seaside’s bandshell. He came to the States in 1968 as a refugee, striking out alone from Bratislava following his people’s revolt. Max does magic tricks and acrobatics but is most famous for his juggling, which he learned as a small boy from his grandfather, a celebrated performer with the Prague Circus. He can juggle just about anything — cocktail shakers, seashells, rubber boots — and he’s always practicing. I see him from my office window walking back and forth along his balcony, his neck craned upwards, tossing objects into the air as he moves. He has an act where he juggles three apples and takes a bite out of one as it flies past his mouth until only its core is left. Before beginning, Max brandishes an apple in front of his audience, announcing that he will leave only the “meedle.” He’s been here for 20 years but still struggles with English. We tried correcting him for a while but eventually gave up. We all manage to get Max’s drift anyway. He’s teaching me how to juggle and I’m up to three oranges. According to Max, I’m a natural. “Honkie dory,” is how he rates my progress. Next, he says we’ll move on to things that are braidable. He means breakable but I let it go.

***

“Some of it’s magic, some of it’s tragic…” It’s Hazel’s voice coming from the laundry room. She’s wearing headphones and singing along with Jimmy Buffett. She loves country and western, claiming it’s the only music that speaks to her. Hazel moved here from Memphis after her divorce. She told me she left her husband flat the day she found one of his notes on the kitchen table signed with both his first and last name. They’d been married 22 years at the time. She swears that one thing tore it.

“He was altogether too tight-assed,” she said. “That kind of thing can rub off.” She works at “Sunshine’s,” the fruit market at the Seaside Mall. Its slogan, written on the side of its trucks and on the clerks’ aprons, is: “If it’s fresher, it’s still growing.”

Even though a large sign in the front office reads: “No Pets in Rooms,” I make an exception for Hazel. Her little Scottish terrier Angus was the only thing she’d asked for in the divorce settlement so I let her keep him. It causes a lot of complaints from summer guests who call up the front office when they hear Angus barking. “If I had known you took dogs,” they’d whine, “I’d have brought my Scruffy, or Mr. Jingles.” Since her divorce she’s heavily into self-improvement and is enrolled in a six-week workshop for divorced women at the local college called “Taking Back Your Life.” She says she’s in better shape than most of her classmates.

“One woman told us most afternoons she sits in her car outside the apartment building where her ex lives. Hour after hour she just sits.”

“Did she tell you why, Hazel?” I ask.

“She says she can’t let go.”

Hazel and her husband were together 40 years. He left her for a woman who is three years older than their daughter. Sometimes late at night Hazel appears at my desk with her basket of nail polishes and cosmetics. “How ’bout a facial, sweets?” she asks brightly. She thinks I should spruce up my look, get with the times, and leaves pictures from fashion magazines where I’ll see them, with handwritten notes attached. “This would be darling on you,” or “Just think about it,” they read. I’d rather stick with what I know, I tell her. There is little enough about me I still recognize, I tell myself.

***

It’s the second week in November. Freezing rain lashes the deserted boardwalk. We’re all in the lounge chatting and drinking, bundled up in sweats and wool socks. We’re comfortable together, the five of us. There seems to be a bond created among those who stay when everyone else has moved on. Seymour is holding court, a book on his lap as always. This one is called “The Inner Child Workbook: What To Do With Your Past When It Just Won’t Go Away.” Seymour is a retired psychotherapist who came here to work on a book after closing his practice in Pittsburgh. He specialized in treating phobias but his fascination with human behavior is far reaching. Most of his days are spent reading psychiatric journals and one of the walls in his bedroom is stacked knee-deep with textbooks and magazines detailing personality disorders none of us has ever heard of. Last week he told us about a case of obsessive-compulsive disorder he’d just read about. We’d all heard of cases of OCD from Seymour, about people who washed their hands fifty times a day or couldn’t stop themselves from checking over and over again to see if their front door was locked.

“This, ladies and gents, is a particularly unusual example,” he says solemnly. “The patient was a Japanese man from San Francisco who had a compulsion to check envelopes before sealing them to make sure his daughter wasn’t inside.” Seymour pauses for dramatic effect, removing his glasses. “He lived in constant terror that he would mail her away forever.” We all think about this for a minute.

“The poor soul,” says Hazel, who has taken off her headphones to listen to Seymour’s latest discovery. We all make time to listen to Seymour.

“Can’t anything be done for him?” asks Josh, who has turned the sound down on “One Life to Live.”

“Is a doggie dog world,” says Max, looking slightly bewildered. We contemplate this in silence. Max is known for adding things to a conversation no one else can.

“The mind is its own place and in itself can make a heaven of hell, a hell of heaven,” says Seymour, quoting Milton, his favourite author. Seymour is one of those rare individuals able to see the bigger picture and he is at work on a book which as he describes “details how the work of 19th century scientists advanced human thought. I’d walk on the beach with Seymour and seemingly we’d be looking at the same things – the waves, or boats on the horizon. Suddenly Seymour would crouch down on his knees, grab a handful of pebbles and scrutinize their formations and colors. Then he’d come out with a treatise on the last ice age or something equally baffling.

Josh turns back to the tv and flicks the channel to “The Price is Right.” The contestants are lined up behind a console. One woman who’s just been picked from the audience is weeping hysterically. In a patronizing tone, the emcee asks her to get hold of herself. Josh moans like he is in pain. He’d done a stint hosting the gameshow “Tic Tac Dough” in the seventies and feels the business has gone downhill in the days since.

“I used to treat guests on my show like they were friends in my living room,” he announces indignantly. “These jerks practically use cattle prods.”

In his prime Josh had appeared in several shows on and off-Broadway, and landed bit parts in a few Movies-of-the-Week. Hazel tells him she remembers seeing him in a role as a handyman in some ABC film about a house possessed with demons.

Josh groans, taking a deep drag on his cigarillo. “Why do people always remember your least distinguished effort?” He says he knew he was destined to be a performer from the first time he drew breath and is forever quoting lines from productions he had appeared in. On summer afternoons he does recitations on the upper deck for anyone who cares to listen, wearing a Yankees cap to protect his bald pate from the sun. My favourite is a speech he does from Hamlet, which he’d performed in summer stock in Maine years before.

“A painfully under-budgeted production, ladies and gents, but stirring nonetheless,” he tells listeners.

“… For there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so… ,” Josh would bellow above the roar of the ocean, his audience looking up at him warily from poolside, slathered in coconut oil, dazed by the sun.

***

It is a brilliant Tuesday morning in March. I am sending out notes to my past customers on motel stationery, reminding them of what a great time they had here last summer. The paper is imprinted with an unfortunate looking logo, another legacy of the owner. He put it on anything he could find: matchbooks, ashtrays, even the bathtub mats in all the rooms. It’s a line drawing of a crazed-looking sailor with bad teeth standing astride a dinghy, hands on his hips. For starters, the scale is all wrong: he practically dwarfs the boat. And as Max says, “Never to be standing up in a roadboat!”

The tv is on, tuned to the Today show as usual. Elton John is on raving about his recent hair weave. I buzz Josh’ room but I know he won’t answer. It’s before noon so there is no chance he’s up. Josh hates mornings: it’s almost a religion with him. I throw a sweater on and run up to his room. “Elton John’s got hair, Josh!” I shout through the door. “He had it done in France. God, it looks good. I would never have known.”

I hear him snort as he moves to the door. He opens it slowly and winces at the daylight. His head is wrapped in cellophane, held in place with the blue metal hair clips Hazel gave him for Christmas. I can smell the Hair Now ointment he’s been slathering on his head nightly for two weeks. The smell reminds me of the licorice pipes they used to sell in candy stores with the pink speckles on the ends.

“Did he say how much it cost?” he asks groggily. I was afraid he’d ask that.

“Oh, 10,000 bucks or so,” I say lightly. “But, Josh, I’m sure he had the uber-weave.”

“Yeh, like either are an option, Moira,” he says, shivering from the breeze off the ocean. “The way they tip on the Shore, I might be able to afford one by the next millennium.”

Late that night Hazel appears at my desk in her nightgown. I’m still working on my mailing. She sets down two glasses and a bottle of Johnnie Walker Black. “Never get married, Moira,” she says out of the blue. If I’d been ready, at that particular moment, I might have told her that once, in what now seemed like someone else’s life, I had been married, had even been a mother once.

“Hazel,” I’d have said, measuring my delivery, “your advice has come to late.” I’d have told her it is why I never look into the faces of small children. I stand above them, noticing their outfits and the colour of their shoes but never kneel down and look into their little faces.

“No chance, Hazel,” I say, looking up at her casually from my stack of envelopes. “I prefer to travel light.” Although I know Hazel would be solicitous – after all, she is a mother herself – I am not ready to tell my story out loud. She pats my hand and pours us each a scotch. “In last week’s class, our teacher told us divorce was like the death of someone close to us, that we had to go through all the same stages of grieving. And did you know tears of grief have a different chemical composition from all others? Scientists have discovered that,” Hazel says. She looks mystified. I didn’t know that. I only know that grief has its way with you, Hazel, propelling you on a journey all its own.

I had taken Emma shopping that morning. I lifted her out of her car seat and put her down on the pavement beside me. I noticed one of her shoelaces was undone and bent down to tie it. She was wearing her favourites: black patent with red ties, her tap shoes I called them. I tightened both laces and patted each shoe in turn. “All set,” I said, pressing my nose up against hers. She kept glancing down at her feet, conscious of herself the way all toddlers are when wearing something they’re proud of.

“Tap thoose,” she said beaming, pointing down at them. The time on the parking meter had expired and I began rummaging through my purse for the correct change. Frustrated, I ended up dumping the contents of my bag upside down on the hood of my car.

“I need quarters, Emm, got any on you?” I joked, turning toward her.

That’s when I heard the noise, a noise that won’t let go of me. Her scream. And then the silence. Something must have drawn her to the road, a dog in a car window maybe or the laughter of other children. I will never know. I’d replayed the scene countless times since, asking myself all the what if’s but the feeling I cannot escape is that I wasn’t careful enough: I did not take proper care. John my husband never consciously blamed me, never spoke the words, but he didn’t have to. He said it in the set of his shoulders at the table and in the detached way he spoke my name. He said it every time he refused to talk with me about Emma. I finally realized it could never, simply, be the same. So I walked away from that life to this, where summers are a blur and where in winter it is easy to disappear.

***

Hazel is thinking of moving on. Her son has been asking her to move down to Miami with him and last winter I heard her complaining of the cold for the first time. I tell her she should go, to think of it as her next adventure. “You could set up a little business: Think of all those blue-haired ladies needing their faces exfoliated.” “I’ll go if you come too,” Hazel protests. But she knows I won’t. Seaside fits me for now. Come spring, there are rooms to be aired out, repairs to be tended to following winter’s damage, and always someone needing something. * The pain is in the details, the small things. It’s in the smell of baby aspirin and in watching a mother stoop down to painstakingly wipe her child’s dirty face. It’s remembering the sound of Emma’s voice thick with sleep, calling for me after a bad dream, and in seeing a line of tiny baby clothes hanging out to dry. Things I cannot always avoid.

For a long time after the accident, my dreams were of things uncompleted, being stuck somewhere with no clothes on, or rushing to board a plane and the gate closing in my face. The only dream I’ve ever had of Emma was one which began this way: I am waking from sleep in my canopied bed back in Minneapolis. From the quality of light in room, it seems to be close to daybreak. I turn on my side and find Emma in a deep slumber beside me. She’s kicked her covers off and is curled in a ball halfway down the bed. I reach down, gently pull her up beside me, and cover us both with the quilt. She stirs, wraps one little arm around my neck and snuggles in.

This winter I’ve taken to bundling up and heading out for long strolls along the boardwalk. Lately I go alone: Seymour is off to Boston for six weeks, taking part in a study on agoraphobia. Max has gone home to Hungary to be with his mother who is ill, and Josh practically lives at the restaurant these days, working double shifts and saving for some radical new hair transplant that Seymour heard about from a dermatologist. I just got a postcard from Hazel. She says Miami is a dream and that she’s just signed up for a course in conversational Russian. “If you get to missing me too much there is a room here waiting for you,” she writes. It’s signed, “Forever, Hazel.”

The midway is closed down until spring, the fronts of all the game booths covered tight with tarpaulin. Seats on the ferris wheel creek as they rock in the wind overhead. In the arcade “Madame Fortunato the Mystic” sits frozen behind a pane of glass, patiently awaiting a coin that will bring her back to life. A few hardy vendors sell snacks and hot drinks from their carts, but business is scarce. By this time I know them all by name, where they came from and how old their children are. They know me simply as Moira, the motel lady.

Shivering, we stand together sipping coffee, looking out to sea, silently counting the days until spring.

This story is based on my poem called “By the Wayside”

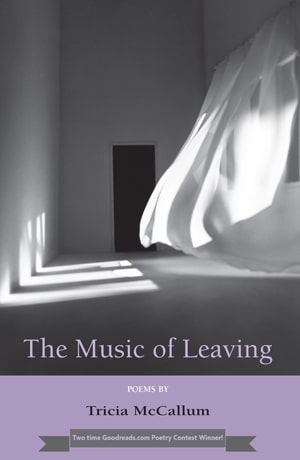

A sequence of my poems has been published in a hardcover book entitled The Music of Leaving Poems by Tricia McCallum

A sequence of my poems has been published in a hardcover book entitled The Music of Leaving Poems by Tricia McCallum

Thanks for sharing