I can’t step into a church without being reminded of Leo.

I see him, leaning heavily on his cane, waiting in the vestibule

to usher the parishioners to their seats,

his labored gait up the aisle, one leg stiff,

the shoulder of his Canadian Legion jacket strewn

with medals and ribbons.

In the stillness the rubber tip of his cane

squeaks loudly against the polished floor.

The star resident at her mother’s boarding-house,

my friend Linda said we should visit him.

He’d insisted,

and there had been toffees promised.

Restless and bored one spring day I relented,

followed Linda home and climbed the stairs lazily to Leo’s room.

Unlike the others his door was open.

There was Leo, lying on his bed, his cane alongside,

rest the only respite from his affliction.

Come in, close the door.

Feed my bird Charlie.

I worried then about telling my mother this.

But Leo wasn’t a stranger.

Everyone knew Leo.

Father Blackwell told us in catechism class

it was men like Leo who had kept us free.

The shabby room smelled of wet wool

from clothes drying on the radiator

and of Old Sail, his pipe tobacco.

A bowl of sweets beckoned by the bed.

Charlie was bustling about in his cage.

Sit beside Leo, honey.

A good Catholic girl, I did as the hero said.

The bristles of his beard stung my face,

his breath turned to a rasp.

I smelled something fetid on his breath.

When he released me

Charlie was singing,

still.

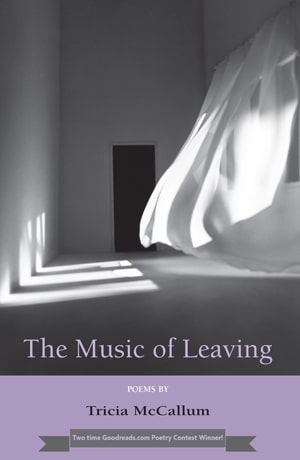

A sequence of my poems has been published in a hardcover book entitled The Music of Leaving Poems by Tricia McCallum

A sequence of my poems has been published in a hardcover book entitled The Music of Leaving Poems by Tricia McCallum