by

Tricia McCallum

“With a sharpened pencil/or similar tool/clean the dirt from the tin box/Under the cracked paint find the rust/Scrape to where it’s raw/stark in the sun/so bright it hurts/Then/write.”

It’s war torn and sepia-coloured now, curled sharply at the edges, but the little scrap of paper containing this verse has long been a treasure of mine, a template for any poem I write. Titled To Myself About Writing Poems, for years now it has been posted within my line of sight wherever I work. As I write this it is taped to the upper right-hand corner of my computer monitor, above the electronic digits announcing the time of day. Its first home 20 years ago was atop the carriage return of my old manual Smith-Corona, its next atop my IBM Selectric, then a Mac 512.

I have no idea where the verse came from or who wrote it, but I‘ve often longed to read the poems that came from that author: I sense instinctively that they would be wonderful.

The verse echoes Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s advice to her fellow poets: “Keep back nothing.” I’ve long put into poems what I couldn’t bear to express out loud, either because the thoughts were too painful, intimate, embarrassing, or revealing. Emily Dickinson pulled no punches. She said “I know it is poetry if it blows the top of my head off.” I’m with Emily. I know I’m onto something if I find myself cringing as I compose one, or stop for a sharp intake of breath before plunging on to the next line.

I have been hearing about the resurgence of an interest in poetry since the tragedy of September 11th, both the writing and reading of it. It is no surprise to me: it is a place to go when all other comforts fail us. When my mother was ill many years ago, poetry was a place for me to put my anger and despair. At night in her home I wrote about what I saw, what I felt. Many of the stories conveyed in these poems I have never told aloud. It was invariably the details that I would focus on in those pieces: the way her hair rose from her forehead, the incongruity of gorgeous summer days piling one upon another while she lay in that room, the sunlight that flooded the bedside table crowded with medications, the way a particular slant of light fell on her face as she slept. “Before you wake this time/I memorize your face/bathed in summer light/ aristocratic still.”

May I Have This Dance? was written the week after she died. Writing this one was a way of helping me deal with a wearisome guilt that lingered. The poem relates what happened on one of her better days that last spring. As I changed her bedding, she had asked me to dance with her to a song on the radio, the way she so often did, ceremoniously, when I was a child. Impatient with her and expecting the nurse, I refused, offhandedly. “Back to bed /I say again/No time for that/And we stand mired in the here and now/Waiting for the doorbell to ring.”

In Grade eight, I had an unrelenting crush on a tall lanky boy in my class. He reminded me of a young Anthony Perkins and was the first boy I had ever paid much attention to. We were fast friends and hung around with a large group of boys and girls. One day while walking home from school he presented me with a small navy blue velvet box, and my heart stopped. Inside was a ring with one perfect pearl atop it. As I caught my breath he asked might I give it to a girl for him, a mutual friend, since he felt rather intimidated at the prospect?

I went home holding back tears and committed my grief to paper. I only remember the piece sketchily now, something along the lines that no one would ever love me enough to give me something so impossibly beautiful. It doesn’t rank as one of my more transcendent efforts and ran about 14 verses. But in an indefinable way, it helped get me back on my feet. The catharsis had begun.

Another later poem is my advice to a former boyfriend after his callous leave. Called Parallax, it reads in part,“My memory has been good to you since you left/taken you and buffed your sharp edges/edited your conversation for wit, sensitivity. / I wouldn’t advise that you come back/Even your eyes aren’t that blue.” This piece served as a place for me to put my disillusionment, my heartache. It was also pure therapy, the chance to royally tell him off. It somehow blunted the dreadful ache.

My father’s death several years ago was sudden and it was many months before I was able to give form to my loss. When the poems came, they came in a torrent, over the course of many long nights, as always describing specific moments, tiny details of times together –- one twilight evening at a community pool when he watched me execute a dive he had taught me…catching a glimpse of him as he sat unawares by my mother’s hospital bed… a description of his lovely, soulful hands lying still atop a bed sheet… after his death finding an old photo of myself and my two sisters tucked deep in his drawer. “Under the cracked paint find the rust…”

Marc André called poetry “the sister of sorrow,” to me a worthy definition. When people read my poems for the first time their reaction is often the same. “Why are they all so sad?” The poet Shelley had the best answer to that: “Our sweetest songs are those that tell of saddest thought,” he said. For me, happiness seems best lived and fully enjoyed. It has never presented itself to me as fodder for verse.

It is always poems that have mirrored my life’s journey, provided my touchstone, helping me come to terms with this life of mine.

They will always be my sweetest songs.

-End-

Tricia McCallum is a poet and freelance writer. A manuscript of her poems is entitled Too Cold For Snow.

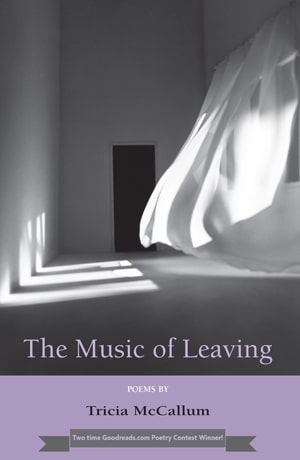

A sequence of my poems has been published in a hardcover book entitled The Music of Leaving Poems by Tricia McCallum

A sequence of my poems has been published in a hardcover book entitled The Music of Leaving Poems by Tricia McCallum