Arlene was due any minute. Arlene was the name of the nurse coming today.

I stood at the front door waiting for her to pull in the driveway, the name of the nursing order painted in white block letters on the side door of her car like all the others. Six months ago my mother’s biopsy signalled cancer and she was rushed into surgery. My brother and I sat in the hospital waiting room for nine hours awaiting news, taking turns going for coffee and making trips down to the smoking room on the first floor. When Dr. Schemmer her surgeon finally came in to see us, it was to announce that “the patient had survived and was resting.” The patient. No, we couldn’t see her at the present time, since she would be a long time coming out of the anaesthetic. Then, he announced, mechanically, “I think I got it all. But there are no guarantees.”

Those were his exact words, delivered staccato, as if he was a weatherman reporting on the chance of rain. He gave off the distinct impression that we had personally offended him in some way. We scrambled to think of the right questions to ask, ultimately not registering the answers to any of them. During the weeks in hospital that followed my mother declined steadily, eventually unable to eat and growing weaker by the day. It turned out that she had developed a staph infection which had caused an abscess to grow deep into her back. It meant more surgery, followed by daily suctioning of the site to prevent the abscess from taking further root. She was finally released from hospital under the proviso that a nurse would visit us every day at home to change my mother’s dressings, a delicate process that involved removing the layers upon layers of bandage packed deep into the wound and then repacking the cavity the very same way. As Dr. Schemmer explained: “It will heal from the inside out.”

I had stopped him in the hallway the day they released her to confirm the details of mother’s home care. As usual, he spoke perfunctorily, as if someone was timing him. Standing close to him I noticed how neatly he had clipped his goatee, so precisely it looked geometric. “Of course, the patient is severely compromised, so the healing will take longer than normal.” He turned and headed briskly down the hallway.

I immediately gave chase. When I caught up to him I grabbed his clipboard and pulled him bodily toward me.

“In what world do people talk like that?” I asked him, mystified. “The patient is my mother: My mother has a name.” I was shouting loudly by then. Aggravated, he turned away, and headed briskly down the hall. Two nurses poked their heads out worriedly from behind their station, prompting me to yell even louder.

“Her name is Margaret. It is Margaret.”

[divider type=”short” spacing=”20″]

I heard a car in the driveway. At the front door I watched as a large matron got out of a blue hatchback carrying several plastic bags. It was Arlene, an hour and a half late.

She was sweaty and flustered. “What a day,” she said, bustling through the door without a greeting. “My son Brent has the flu and I had to have mother come and watch him.” Without stopping for breath, she continued. “I’ve been trying to scale down to part-time for months but they’ve always got some staff problem down there.” This was our second month of home care and mother and I had watched a procession of nurses come and go. Some were born to the job, signalling their compassion with the simplest touch of their hands. To others it was just a job. My instincts about them had grown razor-sharp.

“Arlene,” I said, cupping her elbow. “Let’s go in to my mother. She’s waiting.” My mother made an attempt to sit up in bed when Arlene came into her room. Mom extended her hand and I introduced them.

“Hello, Margaret,” Arlene said, without looking at her. “Hard time of it, eh?” She began unpacking her equipment and laying it out on a small table beside the bed. Meanwhile, she talked non-stop. We learned about her husband’s job and the ages of her children, how she loved living in the country and how could we stand the city. These days Arlene was, in her words, up to her keester canning vegetables and fruit for the winter.

“And that mother of mine,” she chirped, dusting her hands with talc and snapping on a pair of latex gloves. “An absolute godsend. She stocks my freezer with casseroles so all I do when I get home is nuke ’em in the microwave. And today, with Brent … What would we do without her?”

I had worked out a system with the other nurses where I would gingerly hold the wound open with gloved hands while they removed the old dressing. Then, using tongs they would begin to fold in layer after layer of continuous gauze. Unavoidably, the opening was exposed to the air for several minutes. My mother’s face day after day had told me the excruciating pain this caused her.

Within minutes I could see we had a problem. The clean bandage Arlene was inserting wasn’t going to be nearly long enough to pack the wound properly.

“This won’t do, Arlene,” I said, and nodded reassuringly at my mother, who lay quietly.

“I’m sure it will be fine until tomorrow,” Arlene said brightly. “It’s only a day.”

For mother’s sake I contained my anger. Fiercely independent all her life, Mom hated being a nuisance to anyone. In her mind, it constituted bad manners. “I’m sorry, Arlene. There seems to be a misunderstanding. This could seriously compromise my mother’s healing.”

Arlene stood upright, held the tongs aloft and sighed. Her smock was too tight for her and she looked as though she was having trouble breathing. “This always happens,” she said, irritated. “It’s one mix-up after another in that office.” She laid a thick wad of gauze on top of the wound and proceeded to tape it down on all sides. “Believe me, Margaret,” she said to my mother, “you’ll be okay with this until tomorrow.” She patted my mother’s shoulder briskly.

I pictured Arlene’s mother in a kitchen somewhere, surrounded by boiling pots and pans, humming to herself, while mine lay there roped and steered.

“How about the hospital?” I said, my voice beginning to shake, the way it does when I’m heading for a showdown. “They must have thousands and thousands of feet of bandages.”

“Ma’am. My shift finished ten minutes ago. I have to pick up my little girl from Brownies.” She began painstakingly to remove her gloves, one finger at a time. I wondered why she didn’t just pull them off in one shot since they were just going to be thrown out anyway. Throughout the exchange, my mother said nothing. She was on her side, half undressed, and seemed to be focusing on a distant spot in the corner of the room.

I remembered our seven-hour drives every summer to New York to see her sister and how she entertained us from the front seat with rhymes, songs and games to last most of the way. When we would start to fidget, she’d turn to the four of us.

“Settle back now, all of you,” she would say, as if including us all in a great conspiracy. “Think lovely thoughts. We’re almost there.” By that time we were all sleepy from the rumble of the tires and this was all the coaxing we needed.

It was my mother’s look of complete resignation in the bed that day that prompted what I did next. I grabbed Arlene by her meaty shoulders, and pushed her forcefully out of the room and into the hallway. Although she had a good 40 pounds on me, she was amazingly easy to maneuver.

“Leave now,” I shouted into her face. “I’ll call the hospital and tell them you’re coming. Give me the number of the fucking Brownie leader. I’ll tell her you’ll be late.”

“There is no need for profanity,” Arlene said, rushing down the front steps to the safety of her car. She said the word profanity in a hushed voice as if it was itself a curse word.

“Don’t fucking tell me what there is need for,” I yelled back, slamming the door.

[divider type=”short” spacing=”20″]

Arlene never did return. I called the home care office and was told to leave a message after the beep. After an hour’s wait, I drove to the corner drugstore, came back with several packages of gauze and finished the job as well as I could.

The next morning Arlene’s supervisor called me. She said Arlene was so upset she was considering charging me with assault. I explained to her briefly what had happened and she assured me that the nurse coming that afternoon would bring the appropriate supplies. After I hung up, I went back into the bedroom.

“That was home care. Arlene is threatening a lawsuit.” Mother shifted on her pillows and took in the information. She broke into a smile.

“Well, if nothing else, she’ll have a story to tell for years to come.”

“It’ll sure as hell liven up the canning season,” I said dryly, and we both laughed loud and long. I leaned down and gathered my mother gently in my arms, savouring the moment. After all that had happened this was still my mother, able to spin any situation on its head and somehow make it okay. She had done it for me so often: when I was eleven and Bill Deals told me I’d never have a real boyfriend, and when my eczema was so bad we had to apply ointment and gauze to most of my body before I put clothes on.

It was time for her nap. I went out to make some tea and when I finished came back and leaned against the bedroom doorway watching her sleep. The light from the window behind the bed was unforgiving on her ravaged face. Dr. Schemmer was right: there are no guarantees. I went over to the window and quietly pulled down the shade. The room was darkening in the steely blue November dusk, the only sound my mother’s raspy, uneven breathing.

Settle, back, mom, I whispered to myself. Think lovely thoughts.

We’re almost there.

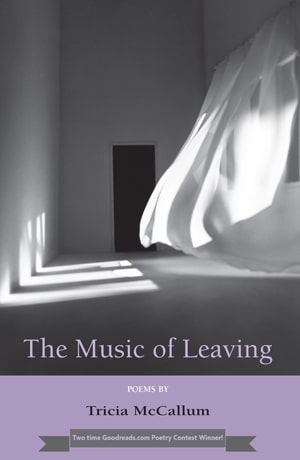

A sequence of my poems has been published in a hardcover book entitled The Music of Leaving Poems by Tricia McCallum

A sequence of my poems has been published in a hardcover book entitled The Music of Leaving Poems by Tricia McCallum