I got to the restaurant early but that’s always the way with me. I am obsessively punctual even when I’m somewhere I don’t want to be. I told the waiter someone would be joining me and he sat me beside a partition covered with imposing jungle plants. Decorating with vegetation, I call it. It’s still big in Toronto, management assuming their patrons would rather examine the variegated tropical leaf brushing their shoulder than the human face sitting across from them. I sat alone feeling conspicuous. I always do when I’m on my own in restaurants. It’s ridiculous, I realize that I have just as much right to be there as the party of four sitting across from me but I never feel as incomplete as when I’m eating alone in a crowded restaurant. I can do lots of things alone, always have. Go to the movies, sit cozily in the back row with my legs stretched out and eat all the food I want. I once ate a super-sub sandwich while watching the China Syndrome. But restaurants are different. There’s something entirely too intimate about dipping a grilled cheese sandwich in ketchup while a complete stranger watches. The restaurant is called “Time Out.” It’s my husband Ian’s favourite haunt these days, famous for its overpriced, organic, low-fat menu. Order anything pan-fried in here and you could be up on a felony. The menu runs more to radicchio and things braised ever so lightly in extra virgin olive oil. Beside each appetizer and entree is listed the precise calorie count. The special today is sea bass. I read this on the announcement which is painstakingly handwritten in calligraphy and attached to the menu with a turquoise paper clip. For $14.95 you get a four-ounce piece of fish boiled in water with a radish salad on the side. I am informed it will set me back 376 calories. I decide to stick with hot chocolate and take my chances.

I ordered, fidgeted, and waited. The drink tasted funny, probably made with carob and skim milk. Is there nothing scared? I wondered. If Ian’s track record meant anything I had at least another hour to wait. It was so like him to pick a crowded, trendy restaurant to do this. He hated scenes and knew I’d be the last person to cause a fuss in a public place. I was raised to be unobtrusive. Of course, he’s still at work. Wheeling and dealing in the markets can make a person lose track of time. The days flip by. Weeks, years, even a whole marriage. I can picture his day timer lying open on his mahogany desk. The entry probably reads: “Susan: 2 p.m. Closure.” And then in brackets, in case he forgets: “Finalize details of separation.” Ian’s a financial wizard. Everyone says so. I can see him as a kid flipping past the comics to get to the stock market quotations. He eats up books on money markets and financial strategies like I do People magazine and his briefcase is always filled with reams of paper covered in columns of figures. At his office Christmas party last year his boss told me in reverential tones that Ian was the most brilliant analyst he’d ever met. At our wedding 12 years ago I introduced my new husband to an old dear friend of mine. They exchanged small talk and she asked him what he did for a living.

“I take advantage of other people’s money,” he said simply, sounding anything but apologetic. He never talked much about his work. I was a writer and I think he figured I simply wouldn’t understand. He was right: I was of the school that my finances were in order as long as my bank overdraft was still in play. I had loved Ian once, loved him so much that I found his assurance and obnoxious comments ascerbic and witty. He was dating my roommate Chris when I first met him. I was away from home for the first time, in my first year of university, and testing out my newfound independence. Chris and I shared a two-bedroom apartment in a rundown house miles from the campus. Ian had a car and picked us up for class faithfully every morning. The three of us got along famously. One night we were at a football game at school and in the row ahead of us a girl was sitting with a tiny beagle puppy in her lap. I asked her if I could hold him for a while. We were never allowed animals at home because of my brother’s asthma. The next morning the doorbell rang and Ian was standing there with one of the puppies in his arms. Behind him was a box filled with puppy chow, rubber toys and a tartan leash. He had found out where the girl had got the pup and bought the last one of the litter. I scooped up the pup from the basket and held him to my cheek.

“I’m calling him Howard,” I shrieked. I’d always loved dogs that had the names of people. When the term ended Chris went back to her hometown to work for the summer. I moved to a smaller apartment and worked two jobs, struggling to save for the next school year. Ian stayed in town too, and I heard he was working in construction. We ran into each other downtown in the middle of July. I had some time to kill between shifts and was window shopping. “Let’s have something cold and you can tell me all about Howard,” Ian said. His face was deeply tanned from working outside. He looked like a young Anthony Perkins. We ended up spending five minutes talking about Howard and the rest of the time about us. It was effortless being with him. We were already friends and everything else seemed like a bonus. I called Chris to tell her about Ian and me. She wasn’t surprised or even disappointed. “Ian and you were always better suited anyway.” Two weeks before school started he moved in with me and Howard. He had four years of business school ahead of him and I was working on a degree in journalism. “You’ll be the Canadian Warren Buffet,” I told him. He was sure I would land a Time cover story mere minutes after graduation. We never had any money but it didn’t seem to matter. I learned a dozen different ways to cook Kraft Mac and Cheese which I’d present with great fanfare on the evenings we managed to spend together.

We were mad about each other. At night we’d curl up together under blankets and share our dreams. We hung the plastic bride and groom from our wedding cake on our front door. Our favourite song was “Moon River” and every year on our anniversary we’d put the 45 record on our vintage turntable and dance cheek to cheek around the living room. After graduation we moved to Toronto. I was writing for a small alternative newspaper and publishing stories wherever I could. Ian had graduated with top marks in his class and landed a job at a respected financial house. He was working ridiculous hours learning the ropes. The little time we did spend together he talked about business almost non-stop, in a language that was foreign to me. Through my work on the newspaper I had swung more politically left than ever. It seemed we couldn’t agree on anything. His associates were the people my newspaper lampooned. One of our cartoonists called them “the suits.” I read his firm’s name in headlines all the time. I didn’t know the precise details of what he did at work but was well aware that Ian was the financial brains behind several corporate takeovers in Toronto. He’d go out for drinks after work and head straight for his desk when he came home. One night I told him he had to slow down. “Don’t take life so seriously, Ian. It’s not permanent.” “You didn’t used to be so flip, Susan,” he said. “Not all of us have time to save the world. Some of us have to work for a living.” One morning before work we heard a story on the radio about the numbers of homeless who were freezing to death on the streets of New York. “Don’t these people have any families?” he said, sounding annoyed. He began discounting my opinions, making them seem inconsequential. He seemed to stand for everything I detested. When I spoke it was as if he was just counting the seconds until it was his turn. I’ve tried figuring out what caused the change in Ian. Maybe the tendencies were there and I ignored them. He worked harder than anyone else at school but I used to admire that in him. Last month I moved out of our house on the Danforth. We agreed I would take Howard; he barely looked at the dog anyway. We’ve seen each other a couple of times since I left. The last time over drinks, he said we should try again.

“I have an investment in you, Susan.” Even now, Ian was translating everything into debits and credits.

I tell him it’s not me that he wants anymore. It’s the young girl he fell in love with 15 years ago who put her own needs behind his. I tell him that I want back the man I married, the one who brought me a puppy with a red bowtie around its neck. I’m on my third hot chocolate and there’s still no sign of Ian. I remember when we first started dating how he’d always show up an hour early. I pay the cheque and step out into the bitter cold. It’s beginning to snow. I glance across the street and notice Ian pulling up in a cab across the street. He steps out of the back looking frazzled and annoyed, his trusty cell phone cemented to his ear as usual.

I turn up the collar of my coat and head for my favourite restaurant three blocks down Yonge Street, a greasy spoon where the French fries are out of this world. This story is based on my poem “The Castoffs”.

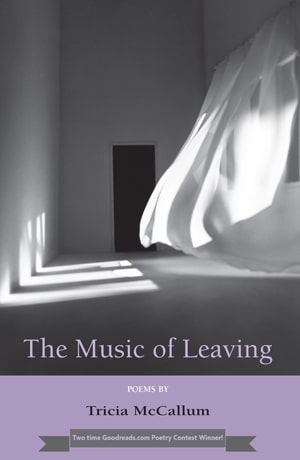

A sequence of my poems has been published in a hardcover book entitled The Music of Leaving Poems by Tricia McCallum

A sequence of my poems has been published in a hardcover book entitled The Music of Leaving Poems by Tricia McCallum