Glancing down at my bare feet

I see plainly the feet of my forebears:

long thin finger-like toes that link us,

irrefutably, astonishingly, across time,

these claw-like appendages that enabled them

to scale the cliffs of St. Kilda

in search of seabird eggs for food.

Ropes tied to their waists

barefoot Kildamanes as young as four

rappelled off the island’s vertical rock faces,

two sea stacks jutting out of the Atlantic

like giant pointed teeth.

For hundreds of years this resolute tribe

foraged for the eggs their lives depended on

among the hidden ledges and wind-battered crags

where the gannets, puffins and fulmar roosted,

eggs their only hope of sustenance

in that unforgiving place,

further out even than the Hebrides.

Fishing, incongruously,

considered too dangerous a pursuit.

Salt killed crops stone dead.

Trees steadfastly refused to grow.

Stories say the sea beat so hard in one storm

it blew sheep and cattle over the cliffs,

left villagers deaf for a week.

Survive they did,

surrounded by nothing but birds,

churning blue black ocean and stretched-out skies,

until visitors brought maladies they were defenseless against.

The seabirds owned it first:

it is theirs alone,

again.

I study the ominous hunting grounds of these birdmen,

my ancestors,

I see the spectacular waves battering the shore.

I look down at my feet,

their feet, wiggle my long agile toes

and whisper

in Gaelic,

the only language they knew,

Cuimhním.

I remember.

Photo courtesy of Alex Mahler.

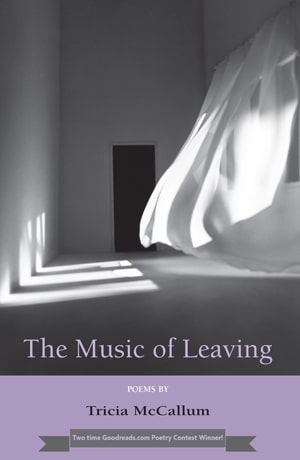

A sequence of my poems has been published in a hardcover book entitled The Music of Leaving Poems by Tricia McCallum

A sequence of my poems has been published in a hardcover book entitled The Music of Leaving Poems by Tricia McCallum