Sister Clara gave me my love of English even though I could have nearly died that day in ninth grade when she announced to the class that I had turned in a perfect exam on Shakespeare’s Henry IV. She stood behind her desk clapping gleefully while I skulked up to receive my paper, my classmate’s groans and jeers resounding at my back.

“Never be ashamed of excellence, Tricia,” she whispered to me as she handed me my paper. I felt there was something in what she said even though I viewed everything the nuns told us as suspect. What did they know of real life, sealed up in their house on the hill, window shades drawn day and night. I used to walk by the convent at night looking for signs of life, hoping to catch a peek of them in thick flannel nightgowns skirting the floor, waltzing with each other, or sipping sherry. I never did though. It seemed nothing moved inside, as if once behind those doors the nuns evaporated, only to magically reappear in a flock each morning on their way down the hill to mass, their voluminous habits flapping wildly in the wind like great shrouds.

All of us at St. Joe’s, especially the girls, revelled in the nuns’ mystery. They weren’t like our lay teachers who kept pictures of their families on their desks and shared with us little details of their lives, like what they did on weekends and their favourite tv programs. Because the nuns were unconnected to life as we knew it they remained unapproachable, even ominous.

Sister Clara was the exception. The rumor was that she had been a businesswoman in Toronto before entering the convent and her worldly style convinced me it was true. She was taller and leaner than the rest. Devoid of makeup and creams she had a face of impossible beauty with razor-sharp cheekbones. The other nuns smelled of chalk and starch but Sister Clara gave off the scent of jasmine, which I assumed was bar soap, an affectation from her previous life. The other sisters generally kept their hands modestly tucked inside the folds of their habits, but Sister Clara had soulful hands with long delicate fingers that she used freely to punctuate her speech.

Her classes were like a reprieve. She often strayed from the curriculum, considered iron-clad by the other sisters, and passed around books on painting and sculpture. She brought in an ancient phonograph and we listened to the music of Tchaikovsky, Benny Goodman, and Nelson Riddle. We learned about the personal lives of authors, how F. Scott Fitzgerald died a broken man, and of Emily Dickinson’s years as a hermit. “You must understand, class,” she’d announce dramatically, “great artistry exacts a certain price.” Once she spent an entire class talking about the Bronte sisters like she’d known them personally. “All three of them sought to hide their feminine identity from editors by using pseudonyms,” she explained, walking up and down the aisles. “Charlotte, of course, was Emily’s greatest fan …”

Every Monday morning we’d come in to find another of her observations written on the corner of the blackboard in her delicate script. I can still remember many of them. One was: “A reader finds little in a book save what he puts there. But in a great book he finds space to put many things.” Another read: “If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry.” Under this one was written the author’s name, Emily Dickinson.

I figured loneliness was something Sister Clara knew about since she was so unlike the other sisters. She had witnessed their unpredictable behavior as we all had, like the morning when Sister Rosalind, our principal, bounded in to our classroom unannounced and sailed over to where Dennis Gray was sitting. Our class was divided into two groups, 10A and 10B, according to academic performance, a witless setup that struck me as a self-fulfilling prophecy. My friend Dennis was slouched over his desk, as usual. He hated school and didn’t try to hide the fact. Sister Rosalind shoved his hands out of the way, threw open the lid of his desk and began tossing his books out onto the floor. “We’ve decided it would be best for everybody if you were to move in to the 10B class. Collect your things and come with me.” Everyone knew about Rosalind’s manic whims – Rosie the Riveter we called her. Dennis reluctantly followed her but not before making a hilarious face to the rest of us behind her back. As he walked past her desk, Sister Redempta called out to him, “You show remarkable grace under pressure, Mr. Gray.” Rosalind pretended she didn’t hear her.

She taught me English Literature all through high school. After my mother died when I was five my father kept us in Catholic school even though he was protestant. He told us sternly it was what she had wanted. Every Sunday morning without fail he dropped me and my four brothers off at mass and waited smoking in the car until we came out.

I guess that’s why Sister Redempta took a personal interest in me. We never discussed it but she obviously knew: it was a very small town. She loaned me one book after another to read, by authors I had never heard of. I devoured them as quickly as she produced them. “It’s important to get different points of view,” she’d explain. “Invaluable to a writer, Anne.” I stood in the freezing cold on Saturday mornings waiting for her to join me at school. I lived for those private sessions, for her singular attention when we’d discuss what I’d read the previous week. When I asked her why she chose a particular book for me, she’d say simply, “We learn the most from what is good.” There wasn’t much reading at my house, only my brother’s comics and my father’s Reader’s Digests, but they seemed insultingly simple and bland. In Sister Clara’s stories, endings were not tidy, things didn’t always come out right.

If I prodded her, she’d occasionally read passages aloud to me. That was my favourite part. I sat transfixed in a front row desk of the empty classroom, learning of independent thinkers and dreamers, and of a wider world I couldn’t wait to enter. I showed her my own poems and stories from time to time and they’d come back to me with her comments neatly penciled in the margins, things like: “Get to the point here,” “Too flowery,” or “Beautifully said, Anne.” My father worried I was taking too much of her free time but when I told her so, she said firmly, “Nonsense, Anne. It is my absolute pleasure.”

One of the poems I showed her was about my mother. In it I described my favourite photograph of her, which was stuck in the corner of my bedroom mirror. The picture is taken in summer at a party in our backyard. A group of women are posing for the camera. They are all laughing, their arms linked, wearing small hats, flowered dresses and gloves. My mother is standing off to the side in a lovely white sheath, her hair hanging loosely over her shoulders. There is a tiny baby girl in her arms, also dressed in white. “I try to piece my memories of her together but memories are not enough,” my poem read in part. I called it “Alone Together.” Sister Clara wrote only one comment in the margin. It said: “Be proud of this one, Anne.”

I was desperate to know about Sister Clara’s life before she entered the convent but knew it was futile. Once I asked her what colour her hair was under her veil and she admonished me to get back to work. Had she ever loved a man, I wondered? Hadn’t she wanted children of her own? I yearned to know her secrets but the gulf between us seemed impassable. One Saturday morning as I was packing up my books to leave, I asked her if she’d ever written anything herself, half hoping she’d reach within the depths of her habit and hand me a brilliant novel in progress. With her command of the language, I felt sure she’d be a marvelous writer. “Not for many years, Anne,” she said quietly. “My efforts are toward God’s work now.”

One night I stayed late to study in the library and heard music coming faintly from her classroom. I crept up to the door and through the glass window saw Sister Clara dancing with herself around the room. The song, Beautiful Dreamer, was playing on the phonograph. She’d played it for us once in class and said it had always been one of her favourites. Her eyes were closed, her arms wrapped around her body as she swayed to the music. Then she picked up the skirts of her habit and turned in one circle after another in perfect time with the music. She looked deliriously happy.

I lost touch with her after high school but had heard she’d left the convent and was working with a food bank in the city. The occasional letters and Christmas cards I’d written to her care of the mother house had never been answered. It was nearly 20 years before I saw her again. I was travelling up Bathurst on the streetcar and at first didn’t recognize her in her street clothes. She was wearing a simple beige suit and sturdy-looking laced oxfords. Her features had sharpened, but she still had a patrician look all her own. Her hair was deep brown, shot with strands of grey, and tied in a knot at the back. So it was dark after all, I thought.

I made my way to where she had sat down and sat down in the seat across from her. After a few minutes I gathered my courage and slid into the empty seat beside her. She was staring intently out the window in a world of her own. I leaned close to her.

“Never be ashamed of excellence,” I whispered in her ear.

She turned warily toward me and I reached for her hand. I knew by her expression she had no idea who I was. The scrawny girl with cat’s eye glasses was now a grown woman with a different face. “Anne Charette, Sister. You taught me at St. Anthony’s. I’m so delighted to see you again.” The words seemed wooden, impoverished.

She looked into my face and smiled. “An absolute pleasure to see you again, Anne. You’re thriving, I see.” I mentioned my work as a freelance writer and she nodded, saying she’d read one of my poems in a magazine once. “You had a gift of expression even a tender age, Anne. It’s no surprise to me.” Even now her few words of praise meant the world to me.

When I’d imagined this meeting I’d envisioned myself telling her so many things, how she’d been the closest thing to a mother I’d had, that she’d given me my sense of who I was, who I could become. But I felt off balance and suddenly shy. I asked about her work with the food bank, hoping she’d share with me her decision to leave the convent.

She talked briefly about her job as administrator and how she pitched in at the food bank wherever she was needed. I pictured her lugging cartons of food around warehouses, even driving the delivery trucks when she had to. “It seems this is where I can do the most good now,” she said matter-of-factly. The crisp way she answered, I realized further questions would have seemed like prying.

I groped for something brilliant to say. “They’re very lucky to have you, Sister.”

She announced her stop was coming up and gathered up her parcels. “I’ve enjoyed seeing you again, Anne. Keep up your writing. Remember – writing is an act of hope.” I recognized it as one of the maxims she’d written on the blackboard years before.

The streetcar lurched off. I turned and watched her walk away, a woman no longer shrouded in black and larger than life. At that moment Sister Clara seemed just like all the other middle-aged women on the street that day, rushing home from work, steeped in their own thoughts. But of course she wasn’t.

She wasn’t like anyone else.

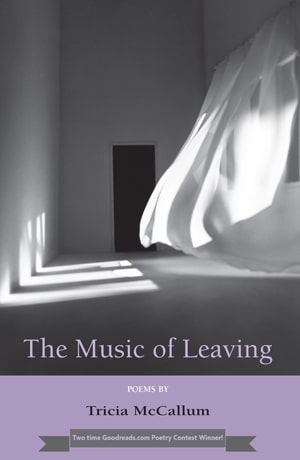

A sequence of my poems has been published in a hardcover book entitled The Music of Leaving Poems by Tricia McCallum

A sequence of my poems has been published in a hardcover book entitled The Music of Leaving Poems by Tricia McCallum